A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

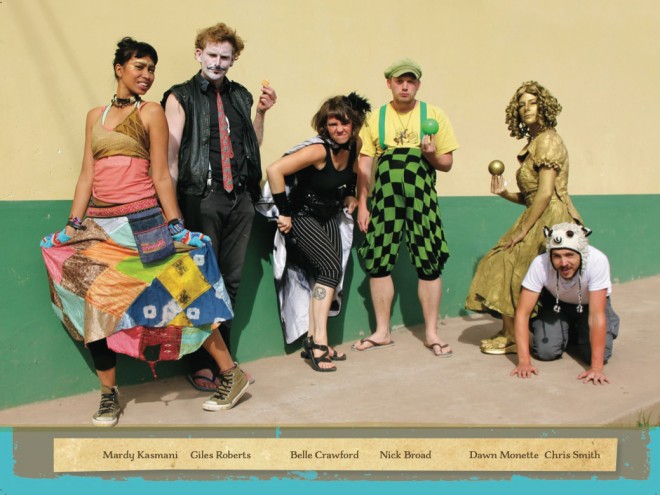

The following is a guest article by Vivian Doumpa and Nick Broad, founder of The Busking Project, an advocacy movement that aims to encourage governments worldwide to embrace this form of free public art in our public spaces. Stay tuned for more on this long-standing form of expression, earning a living - and triangulation - from Nick.

In 1965, Chen Cong was the 12-year-old son of a wealthy bourgeois family in Tianjin, China. His mother was a ballerina and his father was the lead violinist of one of China’s most prestigious orchestras. Chen himself was a promising young violinist, eagerly following in his father’s footsteps.

One year later, soldiers of Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution were confiscating their valuables and destroying their precious record collection. Six other families moved in, leaving him and his parents with just one room. His father kept his job, his mother was forced to become a pig farmer. At one point they were struggling so much that Chen was secretly teaching people how to play the violin in return for heads of cabbage, and riding his bicycle to friends’ houses telling funny stories at meal times in return for food.

His father died. His mother remarried. Chen was alone and destitute. And then something amazing happened.

Through one of his father’s old friends he managed to smuggle a cassette tape of his playing to New York, which was used, through a sponsor, to get him a scholarship to Mannes College of Music. In 1980, Chen escaped China, reached the land of opportunity and completed a four-year Masters in Performance at Mannes, earning straight A’s and the admiration of his teachers.

But although his prospects were high, Chen decided that if he wanted a conductor telling him what or how to play he could return to China for that. Instead, he decided to perform on the subway, choosing freedom and a secure income over the strict and difficult world of the “professional” classical musician. He was still busking 17 years later when I moved in with him.

Chen used to play for 4 to 8 hours every day on the platform of the 57th street F-stop, right underneath Carnegie Hall. He was a wiry Chinese man in white tennis shoes, faded brown corduroys and a blue waterproof camping jacket with a neat comb-over, using a cheap violin to turn this iron-filing filled, stuffy, dingy space into a concert hall.

People who heard him missed their trains on purpose. I saw one man with tears in his eyes listen for a full hour. I saw children dancing, couples holding hands, brows un-furrow, and complete strangers turn from potential threats to companions, as we’d smile at each other, making full-on eye contact. Beggars used to empty their cups into Chen’s clear plastic moneybox. Not even the intermittent shouts of “Bravo!” felt out of place on this subway platform.

One by one his audience would move on, wistfully looking back over their shoulders as the train doors closed, bringing them one step closer to their TVs and their TV dinners.

As William H. Whyte put it, buskers are a means of triangulation: people who have the power to change the way people react to and perceive the space. Chen’s melodies transformed the commuting experience into a recreational experience; he transformed an impersonal space into a place with creative identity. His performance brought people together and allowed them to interact with each other. He was the “eyes on the street”, helping strangers people feel comfortable and safe. These are just some of the ancillary benefits that street performers provide, but which are strong arguments to encourage and celebrate thriving busking environments.

I would love to live in a world where buskers are celebrated and respected for what they do.

Instead, I live in a world where Chen was sometimes spat on. He was told to “get a real job”. He was often harassed by the cops. The first time was a great story: still struggling with the English language, Chen thought the first cop that gave him a summons was trying to sell him a $65 salmon.

As the fines and harassment continued, increasing under the NYPD’s unofficial quota system, they wore him down, eventually convincing him it was time to leave New York, and search for somewhere that will make him feel more welcome.

So, New York has lost one its best features: one of its free, successful and humble placemakers.

Chen was my introduction to the horrendous way buskers are treated. He was also the inspiration for my current career, as founder and director of The Busking Project, a global advocacy movement using the web, a phone app, documentary, events and social media to celebrate and support buskers.

Busking has a long history stretching back to our earliest societies. There were buskers in Ancient Egypt, Rome, Greece and India. From Medieval French troubadours to modern Mexican mariachi, buskers have been performing in public spaces since public spaces were invented. Busking predates the theater and has outlived the CD. It is, historically, the single most common expression of the human spirit: a viable, honorable, and traditional way of making a living.

But today, real street performance is at risk of being licensed out of existence, with permit systems, auditions, fees, written application processes, equipment bans, scheduling and branding making the spontaneous, surprising creativity in public spaces a thing of the past. Negative stereotypes, continual harassment, fines and arrests discourage our best artists from performing in public. These conflicts — and how we can resolve them —will be the topic of future posts.

Watch this space.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.