A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

Over the past couple of months, we have written several times about the need to move toward an Architecture of Place, creating design that makes people feel empowered, important, and excited to be in the places they inhabit in their daily lives. Two blog posts generated some lively discussion around the subject, which has led to new insight about how those of us concerned with the current direction that architecture is headed in can steer things onto a more productive track.

One of the principal challenges facing architecture today seems to be the lack of understanding of how people relate to the context of a site. Words like "community" and "stakeholders" have been bandied around so much that they have become abstract, and the need for individuals to have agency and a sense of ownership of their surroundings is lost in the mix. Commenter Richard Kooyman, for example, argues that:

It's a fad today to say that everyone is 'creative' or to use terms like 'stakeholders' as if by doing so we are now all empowered to make the changes society needs. The reality is that not everyone is equipped or even cares to be creative and real stakeholders are still those that hold the purse strings of projects.

The idea behind good Placemaking, and using a Place-centered approach when designing a building or public space, is not that each individual within a given community is the expert on what that space should look like, but that the community, as a group, has an important expertise about how that space is used, and how the people most likely to enliven it on a day-to-day basis (themselves) are most likely to do so. Another commenter, Gil, makes this case quite well:

At the end of the day it is people's perceptions of how great, or not so great, their places are that matters most...I have yet to attend a public hearing on a proposed project where anything resembling "community attachment" has emerged in the dialogue that emanates from the planners, or engineers, or architects, or those that interpret the rules.

There is a misconception of how community knowledge should be integrated into the design process that we have encountered often in our work around the world. The idea is not that the pen and paper should be handed over to community members to create a final design, but that their needs and concerns be treated as contextual factors that are just as important as the shape of the site, the surrounding buildings, or the site's location within a city. People make a space into a place--or, as Cindy Frewen writes:

When integrated and understanding place and people, design can mean thoughtfully imagined, beautiful, remarkable, moving...Design can help place, if we understand the need to be relevant and connected.

A good designer is someone who thinks creatively about how to develop the most efficient and attractive solution possible to a given problem. For architects, this means creating places that are not just visually appealing, but that are also responsive to the needs that the people who will use those places--not the needs that the architect thinks those people want addressed. When design is responsive (not enslaved) to local needs, it's better for everyone involved: the people who use a place, and the architects, who can point to a well-used and loved place rather than a pristine object. It is our belief that, if more architects were to take a Place-centered approach in their work, it would create a much broader constituency for their work.

It's also important to acknowledge, though, that non-designers are part of the problem, too. Decades of top-down decision-making have led large chunks of the vocal public to be distrusting of architects and urban planners today. In some cities, this has created a culture where any change is seen as bad change, and community involvement can be, for designers, a headache at best. As The Overhead Wire writes, about San Francisco:

When there is an open piece of land, often times people don't think it should be anything. It's kind of crazy, especially with housing costs so high.

While NIMBYism won't disappear overnight, architects and designers can begin to counteract this knee-jerk fear of change by treating the communities that surround a project site as part of the context that informs the building or public space they are trying to create. It's important to remember that, as Ben Brown writes in a recent post on the Better! Cities & Towns blog, most people are "driven by intuition first, reason second." People are very good at intuiting whether or not a new addition to their neighborhood is saying "come visit" or "keep away!"

So how do we communicate the value of understanding people as a fundamental part of a site's context--both to architects who would choose to operate as "lone geniuses," and to members of the public who would rather fight development than try to improve it? As commenter Greg cautions:

I don't think the argument [for an Architecture of Place] will be broadly persuasive until we find a way to take it out of the purely subjective. Because others can and will respond "but that building doesn't make me feel that way," and then there is an impasse.

Thorbjoern Mann, shortly thereafter, suggests that scale is the critical issue to be addressed:

The disconnect between 'high architecture' and the life of places can be traced to several factors. One is the habit of making decisions about projects looking at scale models of the proposed buildings. The larger the building, the more the viewer's attention is drawn to its overall shape, form, geometry, and away from what happens at the ground level where people interact with it.

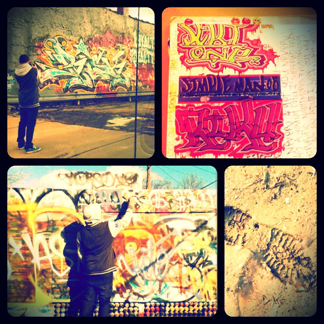

And Graig Donnelly points to an article on the Huffington Post about The Alley Project (TAP) in Detroit that beautifully illustrates how a participatory design process--especially one that builds off of existing community efforts--can create a more powerful sense of place than any of the buildings listed in our Architecture of Place Hall of Shame. Explains TAP's Erik Howard: "Good design speaks to activities and people. Then those get translated into design solutions. The best design is built around people."

We couldn't agree more.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.