A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

Street rightsizing candidates should be evaluated to determine what kinds of changes would be most effective. Our Street Selection guide immediately follows. Once selected to be rightsized, beginning the process of measuring the effort's outcomes can help support that project, and other rightsizing efforts in the project's area and beyond. Our guide to Before and After Measurements (further down this page) can help.

How do you decide which streets to prioritize for rightsizing strategies? It’s important for each community to determine its own criteria, which should reflect the realities of its streets and the people who use them. Here are a few factors to consider, which were informed by conversations with professional planners who have worked on these projects across the country.

The most successful rightsizing projects are those that are desired by a community, and that reflect their vision and values for the street. Indications of a community’s vision for a street and its surrounding area are often articulated in a master or community plan, which could include such goals as improving safety, walkability, bikeability, street life, and/or main street retail. Streets that would provide important pedestrian and bicycle connections in a community, as indicated by a bicycle or pedestrian master plan, could also be good candidates for rightsizing.

Residents or businesses may clash with the state or local transportation department in charge of their street. Community members may advocate for a street to be rightsized that the department asserts is inappropriate, or challenge the department’s assessment of their street’s suitability for rightsizing. Compromise is often possible through a lighter, quicker, cheaper trial implementation, using inexpensive paint and temporary bollards to try out the proposed configuration prior to committing with hard infrastructure.

Reducing the space available for motor vehicles will be more difficult if the street is a major thoroughfare for freight movement or has high vehicle volumes. For example, transportation practitioners interviewed for this project said that they typically do not promote rightsizing projects for streets with more than 20,000-25,000 average daily vehicles without exceptional circumstances and evaluation, and that streets with more than 15,000 average daily vehicles often demand an operational analysis to closely look at impacts before implementing a four to three lane conversion.

Conversely, a street with a low number of daily vehicles is often a more suitable rightsizing candidate. A street with 7,000 or 15,000 daily vehicles can generally handle a four to three lane conversion with no adverse impact on travel times or flow whatsoever, and may be pursued with relatively little study.

However, broader goals for the street should often supersede concerns about impacting traffic volumes. If there are parallel roads that are acceptable to divert traffic, and the community wants a more pedestrian-oriented street, rightsizing may be a useful option regardless of the number of daily vehicles.

Streets with high levels of traffic crashes, particularly involving pedestrians and bicyclists, are excellent candidates for rightsizing projects. Sideswipe, rear-end, and head-on crashes during turns against traffic are particularly likely to be mitigated by converting through lanes to a two-way left turn lane. Further, crash and injury severity will be reduced when vehicle speeds are slower.

Adjacent land uses help indicate the appropriateness of a street for rightsizing. Land uses that generate high numbers of pedestrians and bicyclists, such as college campuses, schools, parks, and local retail, typically suggest that a street would benefit from rightsizing improvements.

The physical layout of the street must be suitable for the changes proposed. For instance, streets with short distances between intersections, especially when they have high traffic volumes, are more difficult to remove moving lanes from without risking negative congestion. Frequency of driveways, bus stops, and space at intersections can create challenges to implementation. Further, intersections should allow turning movements for larger vehicles like emergency vehicles, buses and trucks, where necessary. Emergency vehicles can sometimes improve their travel times where there is a two-way left turn lane, if there is no raised median, because they can easily gain exclusive access to the center lane to create a passing lane. Implementing organizations may need to run traffic simulations of their proposed street changes to predict their functionality and evaluate potential turning, regulation, or signal time adjustments. Few street geometry issues will preclude the possibility of rightsizing, but rather suggest the need for careful analysis and implementation.

Of course, cost influences what kind of redesign is possible on a street. An agency may prioritize rightsizing projects on streets that are already scheduled for repaving or restriping, which can reduce the cost of changes and create the impetus for a conversation about the street's future. The cost of creating hard infrastructure, like neckdowns, can raise project costs considerably compared to simply changing the street’s striping. However, dangerous or poorly functioning streets also have significant societal and health costs that must be considered when evaluating the possibility of rightsizing a street.

Sometimes one jurisdiction, like a city, is interested in implementing a rightsizing project when another jurisdiction, like a state, is not. Depending on the road, it may be possible to transfer the right-of-way to the willing jurisdiction, as happened between the State of Florida and the City of Orlando with Edgewater Drive.

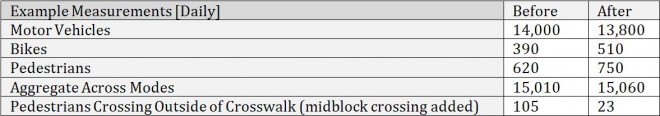

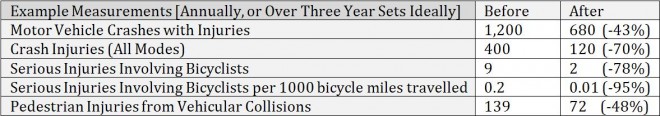

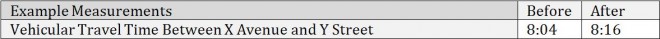

Obtaining measurements of street conditions before and after the implementation of a rightsizing project is crucial to evaluate and communicate the project’s impacts. Before measurements can help define the problem to be solved and the suitability of the proposed solution. After measurements can help ensure that the project has achieved the desired results, and they can also inform adjustments to the project in the future. Publicizing this data can help stakeholders contextualize the impetus and results of the project, and gain public partners and support.

Most statistics are ideally measured over a multi-year period. Periods of three years before and after rightsizing a street are standard, though circumstances could dictate longer periods if a larger sample is desired or shorter periods if preliminary results are required. However, some statistics, such as safety and traffic volumes, may be aberrational immediately after rightsizing implementation as users adjust to the changes. It is also important to consider how other factors impact measurements. The expansion of a nearby parallel route, or other changes to the street network, land use, or population could have as much or more impact than the rightsizing project.

Before and after data is often more necessary for projects in areas where rightsizing has not been previously tried, or when there is considerable debate about whether the approach is appropriate for a particular street or community. The measurements should be selected based on the precipitating factors and goals of the project, and certain targets may be promised to the community as conditions for permanent implementation. Many street or area measurements will be more meaningful when referenced against rates of change in the surrounding area. Below are some best practices for gathering before and after measurements on rightsizing projects.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

We are committed to access to quality content that advances the placemaking cause—and your support makes that possible. If this article informed, inspired, or helped you, please consider making a quick donation. Every contribution helps!

Project for Public Spaces is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization and your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.