A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

I started at the New Jersey Department of Transportation in 1973 right out of college as a civil engineer trainee. For the first twenty years of my career as a transportation planner, I bought into the prevailing belief of the profession that the solution to congestion was to build more and bigger roads. We felt we were not doing our jobs properly unless enough lanes were added to ensure free flowing traffic 24/7, 365 days a year.

I was part of a profession that for five decades viewed its mission as simply accommodating the demands of traffic, whether on local streets or on state and national highways. The quality of life in communities and the condition of the environment were someone else's business; our job was to move cars and trucks as smoothly and rapidly as possible.

Gradually my faith in this "wider, straighter, faster" paradigm of traffic planning began to change. This occurred while I was in charge of a new unit at the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) that had been created to meet with communities, business owners, public agencies and other community stakeholders to seek their support for various road projects. We were supposed to reduce community resistance, which was beginning to delay and even cancel projects. But as time went on, it became clear to me that the real point of transportation projects should be building successful communities and fostering economic prosperity.

Prior to the introduction of the automobile, Americans' concept of what constituted a good road had a vastly different meaning from today. Serving the community and creating an efficient and livable pattern of development were essential values at the center of street design. In short, transportation was fully integrated into land use planning.

The growing popularity of automobiles after 1910 created pressure for the federal government to become more directly involved in financing roads. Spurred on by cries of "Get farmers out of the mud," Congress passed the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which made continuous funding available for states to make road improvements. Motorists and other organized interests began to apply intense pressure to build more highways. In the 1930s many American officials visited the German Autobahn network and returned with a sense of urgency that we must create a national system of high-speed highways. This ultimately led to federal legislation in 1944 to establish the Interstate System and in 1956 to fund it, which ignited the great road building era of the 1950s, '60s and '70s.

Today, it is fashionable to vilify the transportation profession for ignoring the negative effects of large-scale road building on our communities. However, two men at the top of the transportation field during the years the Interstate highway system was shaped--Thomas H. MacDonald, chief of the federal Bureau of Public Roads (BPR), and his top aide, Herbert S. Fairbank--warned that thoughtless planning and improperly placed roads: "will become more and more of an encumbrance to the city's functions and an all too durable reminder of planning that was bad." They recognized that a shift of population to the suburbs was beginning to take a toll on cities.

Unfortunately, the federal government ignored MacDonald and Fairbank's vision of connecting highway development to a broader regional planning approach. As late as 1947, at the annual meeting of the American Association of State Highway Officials (now AASHTO), MacDonald urged his colleagues to do whatever they could to reverse politicians' refusal to subsidize mass transportation. Repeatedly, however, Presidents Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower along with Congress ignored these sensible recommendations for an integrated and balanced transportation network in the various federal highway acts that were enacted.

Starting in the 1950s, the transportation industry mobilized in an unprecedented way to deliver a mandate for a new generation of highways that would eliminate hassles and obstacles to the rapid flow of traffic. Planning in the U.S. became dominated by transportation engineers, while citizens, advocacy groups and planners in other fields saw their influence decline. The transportation profession was remarkably successful in convincing two generations of politicians, developers, construction industries, special interest groups, and the public about how things should be done. With blinders firmly attached, the transportation planners and the nation at large ignored mounting evidence of the unintended consequences of this huge road-building campaign.

By the early 1990s, when the Interstate Highway System--one of the biggest construction projects in human history--was essentially completed, congestion in urban areas was still growing worse and community opposition was stronger than ever to new road projects. Within the transportation profession, there was a dawning recognition that something was innately wrong with the way we think about and design highways.

Yet not knowing any other way to operate, the transportation profession continued to plan new road projects in the same old way: attempting to meet peak demand according to a formula based on maintaining the free flow of traffic at the thirtieth busiest hour of the entire year .

When the inevitable resistance from affected communities arose, state DOTs found that invoking the "national interest", which worked so well during the Interstate era to override community objections, was no longer effective in pushing through the projects. By the 1990s, citizen opposition was able to bring many projects to a standstill.

Meanwhile, evidence was mounting that the wider, straighter, and faster approach was not solving the problem. The Texas Transportation Institute (TTI), in their 2005 Urban Mobility Report, revealed that over the last two decades of the 20th century, congestion indicators had spiraled out of control. The hours each year a motorist spends in congestion had quadrupled.

This was occurring because of the way street and road networks were being planned. Spread out development made possible by the new highway capacity was creating congestion faster than transportation agencies could widen or replace failing highways. Furthermore, mass transit could not serve the new sprawling suburbs and street design made biking and walking all but impossible. This all caused vehicle trips and vehicle miles to explode at a rate many times faster than population growth. Transportation professionals and state DOTs watched these problems worsen but stood aside and did nothing in the belief that their job was building roads and that land use planning was someone else's responsibility.

Now it has become clear with each new fiscal year that construction costs for adding new capacity to roads is escalating sharply at exactly the same time our aging transportation infrastructure demands more and more attention. And in most states, revenue sources have been flat for almost a decade. State legislatures are afraid to mention the "T" word-- taxes. Many roads and bridges built in the highway boom years between the 1940s and 1960's have aged to the point of needing major repairs or replacement, creating a towering backlog of Fix-It-First projects. All of these factors make it far less likely that even the most determined DOTs can build their way out of congestion.

As congestion has worsened in a transportation system focused on high speed travel, so have other social problems. The skyrocketing vehicle miles traveled (VMT) in the U.S. is a major factor in oil consumption and CO2 emissions that spur global warming. Our nation's public health indicators are also taking a nosedive. The National Center for Disease Control (CDC) reports that 25 years ago, only two states had obesity rates above 10%, and none had rates above 15%. Today, in a startling turnaround, no state has less than a 10% obesity rate, and only one is below 15%. Twenty-eight states--more than half the union--are above 20%, and one is above 25%.

1. Target the "right" capital improvement projects first: The first step is to recognize that transportation decisions make a huge impact on land use and community planning--and vice versa. Major investments in roads should be pursued only in communities and regions with effective land use plans in place, which will protect the public investment in new highway capacity. With funds for expanding our road system now at a premium, we can no longer afford to invest in areas whose inadequate land use practices will mean the new roads are soon overburdened. Taxpayers deserve to know that their money will be spent in ways that solve our transportation problems--not in creating new problems. The transportation profession itself needs to accept that road projects carry significant social and environmental consequences. Transportation professionals need to heed Thomas MacDonald's and Herbert Fairbank's advice from the 1930s: "Freeway location should be coordinated with housing and city planning authorities; railroad, bus, and truck interests; air transportation and airport officials; and any other agencies, groups, and interests that may affect the future shape of the city." (Quote from THE GENIE IN THE BOTTLE: The Interstate System and Urban Problems, 1939-1957 by Richard F. Weingroff)

2. Make Placemaking and vision-based land-use planning central to transportation decisions: Traffic planners and public officials need to foster land use planning at the community level, which supports instead of overloads a state's transportation network. This includes creating more attractive places that people will want to visit in both existing developments and new ones. A strong sense of place benefits the overall transportation system. Great Places-- popular spots with a good mix of people and activities, which can be comfortably reached by foot, bike and perhaps transit as well as cars -- put little strain on the transportation system. Poor land-use planning, by contrast, generates thousands of unnecessary vehicle-trips, creating dysfunctional roads, which further worsens the quality of the places. Transportation professionals can no longer pretend that land use is not our business. Road projects that were not integrated into land use planning have created too many negative impacts to ignore.

3. Re-envision single-use zoning: We also must shift planning regulations that treat schools, grocery stores, affordable housing and shops as undesirable neighbors. The misguided logic of current zoning codes calls for locating these amenities as far away from residential areas as possible. Locating these essential services along busy state and local highways creates needless traffic and gangs local traffic atop of commuting and regional traffic, thus choking the capacity of the road system. It also makes walking or bicycling to these destinations nearly impossible in many communities.

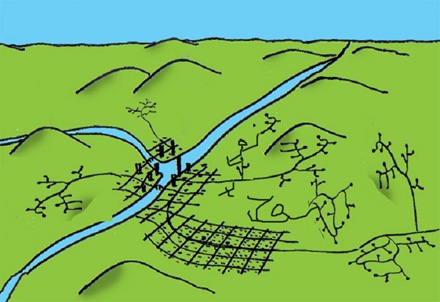

4. Get more mileage out of our roads: The 19th and early 20th century practice of creating connected road networks, still found in many beloved older neighborhoods, can help us beat 21st century congestion. Mile for mile, a finely-woven dense grid of connected streets has much more carrying capacity than a sparse, curvilinear tangle of unconnected cul-de-sacs, which forces all traffic out to the major highways. Unconnected street networks, endemic to post-World War II suburbs, do almost nothing to promote mobility.

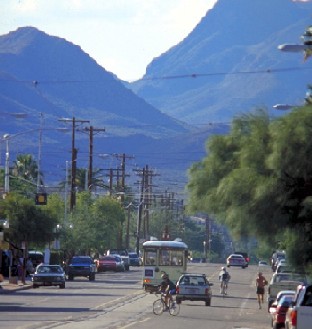

5. View streets as places: Streets take up as much as a third of a community's land. Yet, under planning policies of the past 70 years, people have given up their rights to this public property. While streets were once a place where we stopped for conversation and children played, they are now the exclusive domain of cars. Even the sidewalks along highways and high-speed local streets feel inhospitable. But there is a new movement to look at streets in the broader context of communities (see the Federal Highway Administration's website on Context-Sensitive Solutions.) It's really a rather simple idea: streets need to be designed in a way that fosters desired activities, whether that is local shopping on a Main Street, recreation on a street adjacent to a waterfront or park, or high speed vehicle travel on a freeway. A street's design, management, the traffic speeds fostered , and the modes accommodated should all reflect the specific purpose for that street.

6. Think outside the lane: Last but not least, the huge costs of eliminating traffic jams at hundreds of locations throughout a state will allow for only a few congestion hot spots to be fixed by big engineering projects each year. That means that most communities must wait decades or even a century for a solution to their problems unless we adopt a new approach that incorporates land use planning, community planning and alternative modes of transportation to address ever increasing volumes of traffic.

The transportation profession responded to a mandate from government officials in the post-World War II era to build a new generation of highways for public mobility and national defense. They should be commended for a job well done. A new generation of solutions is needed for the 21st Century, however, and this well-organized and well-trained profession should apply its talents to help us adapt to these new realities. We need a new vision of transportation that truly improves our mobility, sustains our communities, protects our environment and helps restore our physical fitness and health.

The transportation profession can no longer respond to mounting levels of congestion, as well as community and environmental dilemmas, by simply trying to widen existing roads or build new ones. New highways are now packed with cars almost as soon as they open. And today there is just not the money available for that kind of large-scale road building. Most states can't even keep up with the backlog of repair projects.

When I was at NJDOT, we came to realize the 1950's were long past and that we needed a new approach to meet the needs of our citizens. So we began collaborating with the public on solutions that took into account the whole context of communities being served by a particular road--the approach known as Context Sensitive Solutions. Like most people we initially believed that Americans were in love with the automobile and would demand we continue to provide them with bigger, faster roads separated from shopping and neighborhoods. While we did find this response in some communities, we were surprised by how many more communities firmly supported better land-use and community planning.

Americans may always love their automobiles, but that does not mean we want to spend all day stuck inside them. Transportation systems that afford Americans the choice of getting to places without using their cars actually offer more freedom than those where people are solely dependent on the auto to get everywhere. People easily understand this, and can see that a transportation network catering exclusively to cars has harmed our communities, compromised our health, fueled the environmental crisis and made us dependent on foreign oil.

There is nothing un-American about planning communities as a whole, and acknowledging that roads are just one of the elements that create a livable place. This was the common sense that guided our communities until at least 1920. While pre-20th century community planners were by no means perfect, they did create places where transportation was integrated into broader public hopes. The roads and bridges in these areas were built to foster economic development and quality of life in the community, not to hamper it.

If we are to really embrace the concept of healthy, livable communities that serve a diverse population and that make choices for mobility a priority, then we must integrate our transportation planning with other goals and we must design our roads for all users. In short, we must capitalize on the wisdom of our roots.

Many thanks to Ian Lockwood of Glatting Jackson, who helped craft and contribute concepts for this article.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.