A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

Co-Director, Asset-Based Community Development Institute, Northwestern University From Parks As Community Places: Austin, 1996, a publication on the Urban Parks Institute's annual conference.

I want to think with you about what a community is, in relationship to a park. I'd like to begin our discussion with a story from the Sufi Muslim tradition. If you know Sufi stories, then you know that they traditionally begin with the moral - so that people know immediately what the point is. The story is then told in order to unfold, and to comment on, the moral. The moral in this story is: You will only learn what you already know.

Here is the story:

The elders in a village had failed time after time to resolve a difficult problem, and so they invited a very wise person from another village to come and help them solve their problem. And, in time, she came. And when the people gathered to hear her wisdom, the wise woman asked them: "Do you know what I'm going to tell you?" And the villagers shouted: "No! We don't know. We wouldn't be here if we knew." So the wise woman replied: "You will only learn what you already know. And if you don't know what I'm going to tell you, I'm leaving." She left. The village was in an uproar.

Months passed, and the problems didn't go away. The elders debated and planned, and finally they decided to issue a second invitation to the wise woman. And the wise woman returned, and once again she asked her question: "Do you know what I am going to tell you?" And this time they'd been thoroughly organized, and the villagers shouted in unison: "Yes!" They knew a trick question when they heard one. So the wise woman looked out at them and she said: "Well, if you already know, then I have nothing left to tell you" - and she left. And, once again, the village was in an uproar, and the discussions got more heated, and the meetings got longer.

Convinced the woman had something important to teach them, the villagers decided to ask her back for a third visit. This time they were terrifically organized, and she came, and once again she asked her question: "Do you know what I'm going to tell you?" And this time, in unison, half of the villagers shouted, "Yes!" And half of the villagers shouted, "No!" So the wise woman looked out and she said: "Now, will all of those who know what I'm going to tell you tell everybody who doesn't know- that way we'll all know." And she left ... and never came back again.

That night a wise leader of the village had a dream, which she reported to the gathered villagers the next morning. She said: "Last night a voice appeared to me in my dream and told me the meaning of the message from the wise woman." She said: "The wise woman has been trying to teach us that any really important knowledge is already here in our village - in our culture, in our traditions, and, most importantly, in our relationships with each other." She said: "We already know. The only thing we lack is the confidence to believe that we know."

That story has been told in the villages of the Middle East for seven centuries. At the Asset-Based Community Development Institute, we've been on a 30-year odyssey around the United States - visiting most of the largest cities, and a lot of medium-sized ones. And in those cities we have been spending most of our time in the most challenged neighborhoods.

In those neighborhoods - from the South Bronx, and Roxbury in Boston, to South Central Los Angeles, and the West Side of Chicago, the North Side of St. Louis, Hough in Cleveland, the East Side of Detroit - that odyssey has meant a constant barrage of invigorating surprises. Our task has been to meet with old and new friends, and to collect from them stories about what, in the face of immense challenges, is working in their communities. We ask them: What is it, when people look down their block, and around the corner and up the street, and into the park, that gives them hope? What makes them think that if they have a beloved grandchild, and she or he becomes a success - that they don't have to leave the South Bronx; they don't have to leave the West Side of Chicago? That this is a community that has many hopeful possibilities?

Our book, "Building Communities from the Inside Out," is a collection of those success stories. And our attempt has been, over the last four or five years, to sit with people from communities across the United States - often on park benches - and to think with them about the lessons from those stories: What can we learn by studying success? This is an unusual question for a university to ask, because most universities, when they interact with communities at all, ask only one kind of question. That is: How is it that communities can cause so many problems? And what is it that we, who know better, in universities, can do to solve the problems, and sweep up after the messes communities cause?

"We've been asking the same question that our grandparents knew how to ask . . . and that is: How do communities solve problems?"

In our work, we've been asking a different kind of question of communities, and it's the same question that our grandparents knew how to ask, and their grandparents, and their grandparents before them. It's the question that human beings have always asked about communities, until about 40 or 50 years ago, and that is: How do communities solve problems? What are the problem-solving capacities of local people in their spaces?

There's a little church on the West Side of Chicago that had dwindled to 35 people about 15 years ago, and faced the challenge of whether they were going to close their doors, or whether they would stay open. And they thought and prayed and strategized about that for about six months, and they decided: We will stay here, but we will stay here only if we can figure out how to be effective community builders.

They looked around and asked: What do we have here to build with? What are our tools? All they saw was each other - 35 folks in a basement. They said: "Well, that's enough - we could start with that." They looked a little further and saw that they were sitting in a mortgage-free church, and they remortgaged it. With the proceeds they bought a collapsing, abandoned, rat-infested, three-flat apartment building down the block - and then, for the next six months, these 35 folks - old folks and young folks, and women and men - spent their Sunday afternoons teaching each other carpentry and drywalling, and painting and plumbing, and what they needed to know to get that building back in shape. And within six months they had the best-looking building in West Garfield Park in Chicago. They sold it, they bought a second one. They've been doing that for 15 years.

And what do they have out there today? They have a $10-million-a-year community development corporation, instead of a little church of 35 folks. It is not without its struggles, but they can now point to over a thousand units of affordable housing that they have built or renewed in that neighborhood. They can point to 500 people who have jobs, who wouldn't have if they hadn't been there. And it's hard to get in the church on Sunday morning now. They have three services, and lots more than 35 people.

What does it mean? Every once in a while, we would stop in our relentless pursuit of stories of communities who have had success, and we would ask, of somebody who'd become a friend and a teacher: What do you think went wrong in this neighborhood? How did sections of Roxbury become garbage dumps? How did the South Bronx become the symbol of urban decay?

I want to preface my answer by saying that there are lots of explanations for that, and they're complex. We would always hear a word about economy - that the economic context in which our communities live is changing daily, weekly, monthly. And many communities that we work in feel themselves to be cut off from the mainstream economy - feel themselves, in fact, to be useless economically. I think parks have a critical and, as yet, largely unrealized role to play in redeveloping communities.

So when we asked, "What went wrong here?" we would often hear: Look, the economic context changed. In our own city of Chicago we've lost over 300,000 industrial jobs. That makes a huge difference.

The second thing we would hear when we asked what went wrong was a whole lot of testimony about the demonic results of racism - the way in which people continue to be cut out of the mainstream of American opportunities and life - and, there, too, I think parks have a critical role to play, as a celebrator of cultures; as a celebrator of the possibility of building community; as a way of lifting up the gifts and capacities and histories of the many peoples in our cities.

"I think parks have a critical, and as yet largely unrealized role to play in redeveloping communities."

But the lesson that sticks in my mind most clearly, was clarified for me by a great teacher of mine - an African-American woman who passed away a couple of years ago in her early 80s. She and I were sitting on her front porch about nine years ago, and I asked Mrs. Johnson, after another day of her showing me successes - parks coming back to life; housing being built; young people being involved in life with the community; jobs being created - I said: You've lived here all your life, what went wrong here? And we had spoken before about economy and racism and disinvestment, and so on, but that's not what she said this time. She said: The worst thing that ever happened to us, in my community, is that we got put into a prison. Not the kind of prison with barbed wire and bars, the prison I'm talking about is a prison that's made up of other people's ideas about who we are in my community.

I asked her to say a little bit more about what she meant. What she said was: I can't go anyplace else in New York. I can't go down to Manhattan. I certainly can't go to the suburbs - Westchester County or New Jersey, or Connecticut - and talk about my community. Because the minute I open my mouth and say, Hi, I'm Mrs. Johnson - I'm from the South Bronx, I can see what happens to people. What happens to people is that a whole set of ideas pour into their heads. And those ideas are so consistent and so powerful that there isn't room there for any other ideas.

We started thinking about Mrs. Johnson's wisdom, and we started visualizing what she was telling us - that there are images in people's minds when she says the words "South Bronx." There is a kind of map of needs and problems and deficiencies that appears. Mrs. Johnson says to me this map constitutes a prison. [See Illustration 1.]

This always reminds me of the proverbial glass - proverbial because it's half-full and half-empty. All I want to remind us of is that this glass is exactly like every one of us. Every person has some fullness - some resources and skills and wisdom and knowledge, some gifts. But we can confess to each other that each one of us also has some emptiness. Some needs and problems, deficiencies. If we want an organization to work - a university to work, a city to work, a park to work - we'll call people together, even though we know they've got all kinds of needs and problems in their life. We'll call them together around their skills. No community on the face of the earth has ever been built except on the skills and resources and contributions of the gifts of the people who live there.

So what's wrong with this map? This map says to Mrs. Johnson - a brilliant, brilliant community-builder - and her neighbors: The only thing important about you and your neighbors is what you don't have - your deficiencies. And we have spent the last 40 years in the United States building huge systems and institutions, funding them with billions of dollars, whose job it is to amplify this message to communities: You get better and better, communities, at understanding and broadcasting to us your needs and your problems and your deficiencies, and we will give you money. If you want to get connected to the mainstream of public, not-for-profit, and private America, you get connected by virtue of public recognition of the part of your life which is deficient, empty and problematic. It's the way we marginalize people. We define them by what they don't have: Oh, you're too old - over to senior-citizen housing with you. You've got a disability? Let's group you with everybody else that has disabilities, and off you go to the side. Oh, you're too young - we'll put you to the side in filling stations, called schools, until you get filled up ... and then you can come out, and we'll recognize your gifts and ask you to contribute. It's an absolute dead end.

This approach has been invented by nobody but well-meaning folks, and has been adopted, and perfected, by some of the major institutions in our culture, including my own. Somebody once heard that I had a doctorate in social sciences, and she said: Oh, I know what you guys do. You're the people who quantify our misery.

"No community on the face of the earth has ever been built except on the skills and resources and contributions of the gifts of the people who live there."

I plead guilty. I think universities draw this same map, and reinforce it, and thereby set the tone and the tenor and the content of the discussion in relationship to communities. We're not alone. Public-sector funders, media - lots of folks have bought into the idea that's what most important to know about communities is this map.

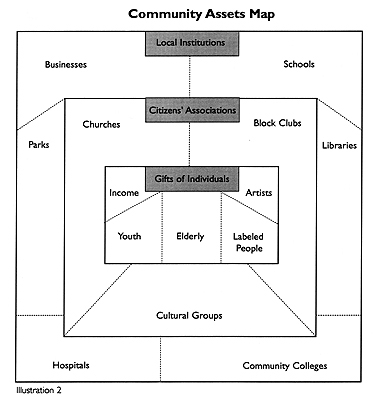

Now, the wonderful news is that, even though this map has determined our policies for the last 40 years in communities across the United States, people are recognizing that it's a dead end; that it's a formula for hopelessness; that it is a path toward funding failure over and over again. Communities who want to move away from hopelessness have echoed Mrs. Johnson, much to our pleasure: That map is somebody else's idea about who we are, and what we need is our own idea. And so they're redrawing their map into a Community Assets Map. [Illustration 2] We are watching what happens when communities recognize that the central pledge of a community builder is to recognize the gifts of the individuals who live there, the gifts of the residents. What would happen if all of us took this simple pledge:

Number one: I believe everybody around the park that I'm interested in, everybody in this community, is gifted. Not just professionals, not just people with degrees, not just people with ties, not just people with jobs - everybody has something to contribute. And number two: It's our job to make sure that everybody contributes their gift.

Parks have been part of a process of institutionalizing the delivery of programs and solutions, by professionals, to folks who are defined as empty, and therefore incapable of contributing to their own community-building agenda. How do we begin to break away from that to rethink what a park is? Can a park be a magnet for the gifts of the people who live around it? Can parks build skills banks? Can parks be resource exchanges? Can parks be, themselves, a learning network?

It is astonishing what you will begin to find if you look in even the poorest neighborhood in the United States. In a four-block area around a park and a school in a very poor neighborhood in Chicago, we teamed up with teachers, parks people and local residents to do door to door interviews, and found that more than 50% of the households had people in them who considered themselves, at some level, to be artists: storytellers, painters, and comic-book writers, people who did theater, and people who did all kinds of crafts. When asked: How many of you would be willing to contribute your arts and culture to the park? - about 80% of the folks said, Of course we would - we've never been asked.

We're sitting in the middle of vast, vast resources, which we have not so far tapped. Many of those people have their gifts already being magnified - not by our institutions ... our parks and our schools ... but by the local voluntary groups in the neighborhood - the block clubs and the churches, and the women's groups and the sports teams. And we're just now beginning to explore what is the local associational life of a neighborhood, and how that can be invited in.

A number of years ago, we were working in an area that was dominated by public housing, where nobody thought there was anything left in associational life. And we took a little look with some friends who lived there - and, in a few weeks, we uncovered more than 320 local groups: women's groups, youth groups, block clubs, card groups, singing groups, sports teams. There was a huge range of activities where people were already out the door doing something. And then, we asked them: Would you be willing to do something more? - connect with your park, connect with your school, build the local economy, connect to young people in trouble - 75% of them, choirs and softball teams, said, Of course we would - nobody's ever asked us.

The lesson, constantly, for us is: There is more in every community in the United States than anybody knows, and the people in it will give more than anybody suspects. We're just beginning to see what a school can be, if we think of it as something more than a place that operates from 8:30 to 3. What if we really did, in fact, use all of the resources inside a school for community building?

What does all this lead to? I think this is leading us to a re-recognition of the critical question of the role of a citizen. I think we're seeing a shift in both language and practice. Parks are involved - parks must be involved - at the center of it. We've got a lot of language out there about emptiness. "Recipients" are thought of as empty people - that need filling up. "Clients," I think, are empty people also. To some degree, "customers" and "consumers" are empty people.

We're very interested in what it means to change the language and the practice from all of the words for emptiness and deficiency, to a language and practice that is about "friends" or "neighbors" or "participants." Or my favorite, and the most powerful word, is "citizen." This is not a citizen defined by legal or illegal status; it's not citizen as somebody who votes every two or four years, although those are important roles. This is a citizen who is understood as somebody who comes out of the door every morning cognizant of her or his resources, ready to join with other resourceful neighbors to do problem-solving and to do community-building. That's what a citizen is.

"I think this is leading us to a re-recognition of the critical question of the role of a citizen."

It's in that sense that your discussions here about parks are not just about parks - they're not just about space - and, really, they're not just about building communities. I really think that you all are at the center of the discussion which will determine whether or not we, in the 21st century United States, have anything that we could even begin to call a democracy. This is a discussion about the future of democracy - if there is a shot at rebuilding a citizen-owned set of activities. Parks are the space; parks can be the magnet; parks can be the places where people are invited to exercise their citizen muscles.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

We are committed to access to quality content that advances the placemaking cause—and your support makes that possible. If this article informed, inspired, or helped you, please consider making a quick donation. Every contribution helps!

Project for Public Spaces is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization and your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.