A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

by Leon Younger,

From Great Parks/Great Cities: Denver, 1998, a publication on an Urban Parks Institute regional workshop.

In 1992, when I was hired to run the Indianapolis park system, it had been in a downward spiral for about 10 years. In fact, the local newspaper had ranked all the city departments in terms of meeting citizens' needs, and the Parks Department was rated second to last. Part of that decline was due to budget cuts; the parks department work force had shrunk from 800 employees to about 350 over ten years. However, in the process of cutting back park services, Indianapolis had lost its whole sense of the value that great parks can have for a city.

Soon after I arrived, the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce did a study on the park system that concluded it needed $100 million in capital improvements. Mayor Steve Goldsmith challenged us to create half that amount - $54 million - in three years, with no additional tax money. We had to either earn it, or get people to invest in us. If we raised the money, we would have a chance to meet the goals outlined in the report in regards to infrastructure repairs.

To meet the challenge, we knew we needed to develop a different kind of fiscal strategy, one that tapped into the abundant resources - not necessarily financial resources - of the neighbors living around the parks, as well as the entire community of Indianapolis. To do that, we initiated a strategic planning process, which helped us identify four types of opportunities - partnerships, efficiency, privatization, and earned income.

In Indianapolis, nobody had looked at the potential of partnerships as part of an overall fiscal strategy for a long time. The Parks Department had about 200 partners but they were "relationship" partners only, meaning that we were funding many of their activities. Measuring the value of contributions by partners is very important. We wanted partners who would contribute dollars or services to parks and programs in a more equitable manner.

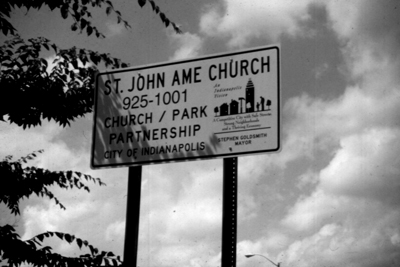

One of the first things we did was sit down with the key leaders in our many neighborhoods, and ask them: "What could this park do for you? What problem could this park solve?" Once they thought about how a particular park could help their neighborhood, they became interested in becoming the kind of partners we were interested in having. For example, we initiated partnerships with local churches that were willing and able to maintain several neighborhood parks near their church, in exchange for a small fee. This allowed us to dedicate union labor to the larger parks where their skills were needed more regularly and used more efficiently.

Neighborhood partnership projects can start small, for example with spring and fall cleanups of a park. In Indianapolis, one strategy we used was to simply set baseline standards for maintenance, and then inform the neighborhood groups that if they wanted to exceed this baseline standard, they could go out and raise the money and get a higher level of service and site amenities.

Many good partnership opportunities grew up around our greenways, which were in an advanced state of neglect. For example, we built partnerships with associations and school districts who could help us build links to the greenways from area institutions. Schools and parks had never been planned together as complimentary facilities, so we began to share investments. This strategy proved successful because we both benefited from the relationship.

Another important part of our strategy was to evaluate what our core and non-core services were, in order to be able to make decisions about where to focus our money and activities. We developed a model that ascertained what our costs were for supporting the activities at all of our facilities, and called this an "activity-based costing model." In looking at what our services were costing us, we had to ask ourselves: should we really be providing this activity, and how much should it cost us to do it? We recognized that we needed a strategy to be able to determine how we could develop a balance between providing what we thought was important with what we could afford.

We measured what the actual cost for us was, for example, if somebody used a swimming pool, or one of our recreation centers. And we found out we were spending much more than we thought. For example, we discovered that one local swimming pool was operating at a cost of $44 per person/per visit. Part of the problem was that these pools were designed for competitive swimming. Most of them were large and deep. However, 80% of the pool users were not using the pools for this purpose. They were only using the shallow end of the pool with their families. So we converted many of our competitive facilities into shallow, zero-depth pools, which we then called "family aquatic centers."

Facilities should be changed to reflect how people use them. Rigorous tracking of program and facility capacity will help you understand where your efforts need to be concentrated, in order to bring the use and facilities provided in line. This data can also help form an argument to eliminate a program that has become institutionalized and eats up money because it is not well attended and is at the end of its lifecycle.

After we conducted our "activity-based costing model," we began to look at what elements of our services were being repeated, and what we were providing that somebody else could do more efficiently. The result: we competed and out-sourced 19 functions within our system, which helped us maintain our budget, and brought new dollars into our system that we used to enhance our facilities and programs. For example, we out-sourced the management of golf, and required each contractor to put in a certain amount of capital improvements. This resulted in a full rehabilitation of all of our golf courses and programs within two years.

We also did a revenue plan where we evaluated all of our available resources. We found that we were pricing many of our services for the 20% who could not pay instead of for the 80% who could. Instead, we began to price our services according to the benefit received. The idea is that if a person goes to a park and is able to reserve a picnic shelter for their personal use or for the use of their church group, they have retained a benefit that is not available to everyone else. Our thought was that they should pay for this kind of benefit. Benefit-based pricing became our method to determine price and we changed our pricing policy to reflect this thinking. However, we also realized that there were certain subsidies that people needed and so we priced our services in conjunction with a subsidy strategy for each program area that included a different subsidy level for seniors, people with disabilities, adults, youth, day camps, disadvantaged youth and adults. Overall, we knew that we were charging much less for our activities in terms of what people would pay, and so we raised our prices based on benefits, but we also established a sliding scale, through business and individual sponsorships, for people who couldn't pay for our services.

The real challenge was to bring our programs up to a high standard and communicate our enthusiasm to the people. People love to help. However, you need to create the mechanisms to allow them to invest in the park system. The challenge is to find people who have vision and who also know how to solve problems.

By 1995, the park system was no longer ranked at the bottom of all city departments; it was now ranked number 2, right below the fire department, and had been a finalist in the NRPA Gold Medal Award program. We made that leap by developing successful partnerships and by developing a fiscal strategy that tried to use all the resources already available to us in the community more effectively.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.