Introduction

In 1975, Project for Public Spaces was founded by Fred Kent, Kathy Madden, and Steve Davies to prove why public space matters. Since then, the organization’s mission has grown to help hundreds of thousands of people around the world understand and improve the public spaces in their own communities through education, convening, grantmaking, and on-the-ground design and planning services.

In recognition of our 50th Anniversary in 2025, Project for Public Spaces invited this growing community of public space professionals—including planners, designers, place managers, public officials, artists, researchers, activists, and others—to participate in a State of Public Space Survey. The response was overwhelming, with over 700 respondents from around the world contributing their insights to help us better understand the biggest challenges and opportunities facing public spaces today.

The results also reaffirmed some of our core beliefs about public space. Firstly, the diversity of respondents and responses demonstrates the potential of public spaces to act as multi-solvers. As the costs of healthcare, disaster relief, and the justice system climb ever upward, study after study has found that we could be saving millions of dollars by addressing many of the root causes of these problems at the crossroads where they come together—in the public realm. Instead, we spend millions more downstream, inefficiently and ineffectively trying to solve these problems one by one.

Secondly, in order to fulfill this unique role, we must rethink the way we fund, regulate, and capture the value of public space. Much like parenting, successful placemaking requires an approach that puts the holistic care of a public space at the center, and wraps around resources and services that allow the caretakers to do their work well. Until we do this, our cities and towns will fail to unlock the full potential of our parks, streets, markets, public buildings, and other civic infrastructure.

The results of this survey offer a snapshot of the state of public space at a critical moment.

For the United States, in particular, these results offer a baseline measurement of the health of our public realm, prior to the widespread cuts under the new administration. As the national landscape continues to evolve, we plan to track progress on these issues carefully, and continue to help civic infrastructure champions navigate what comes next.

Who Took the Survey

Because public spaces require contributions from a wide range of professions and sectors, there is no comprehensive data for the broader field of public space professionals or placemakers. However, the demographic and professional makeup of these survey results offer an informative cross-section of the field, which aligns with other data Project for Public Spaces has collected in the past through its events and communications.

The survey gathered responses from over 700 individuals across 57 countries and 48 U.S. states, with 76% of responses from North America. Respondents represented a diverse mix of sectors and an even wider diversity of industries, with City Planning representing the greatest share at only 16%.

Data Dashboard

Demographically speaking, while the age range reflected an even split from age 20 to over 60, the majority of respondents had fewer than 10 years of relevant work experience in the field, perhaps reflecting the rapidly diversifying nature of public space work. In terms of gender, 63% of respondents identified as female, 20% higher than the field of city planning, while 3% identified as non-binary or chose to describe their gender, nearly double the proportion of the overall U.S. population that identify as non-binary or transgender. Among North American respondents, 29% identified as people of color, which is 13% lower than the total U.S. population but 8% higher than the field of city planning.

While 61% of respondents indicated that public space was their full-time job or part of their full-time job, a noteworthy 30% of respondents contribute to public space as volunteers, and the remaining 10% as part-time employees or contractors. While successful public spaces often rely upon enthusiastic community involvement, this reliance on volunteerism and potentially precarious workers may also speak to the way cities and towns hide the true cost of public space work from themselves.

Seven Big Takeaways

When our survey asked whether local public spaces were meeting the needs of the community, 32% of respondents said that public spaces were failing, while another 63% said they were doing alright, but needed improvement.

Only 5% of respondents said that public spaces are meeting community needs.

This stark result underscores the pressing need to rethink how our shared spaces are designed and managed, ensuring they fulfill their potential to support community health and well-being, strengthen resilience, and boost local economies.

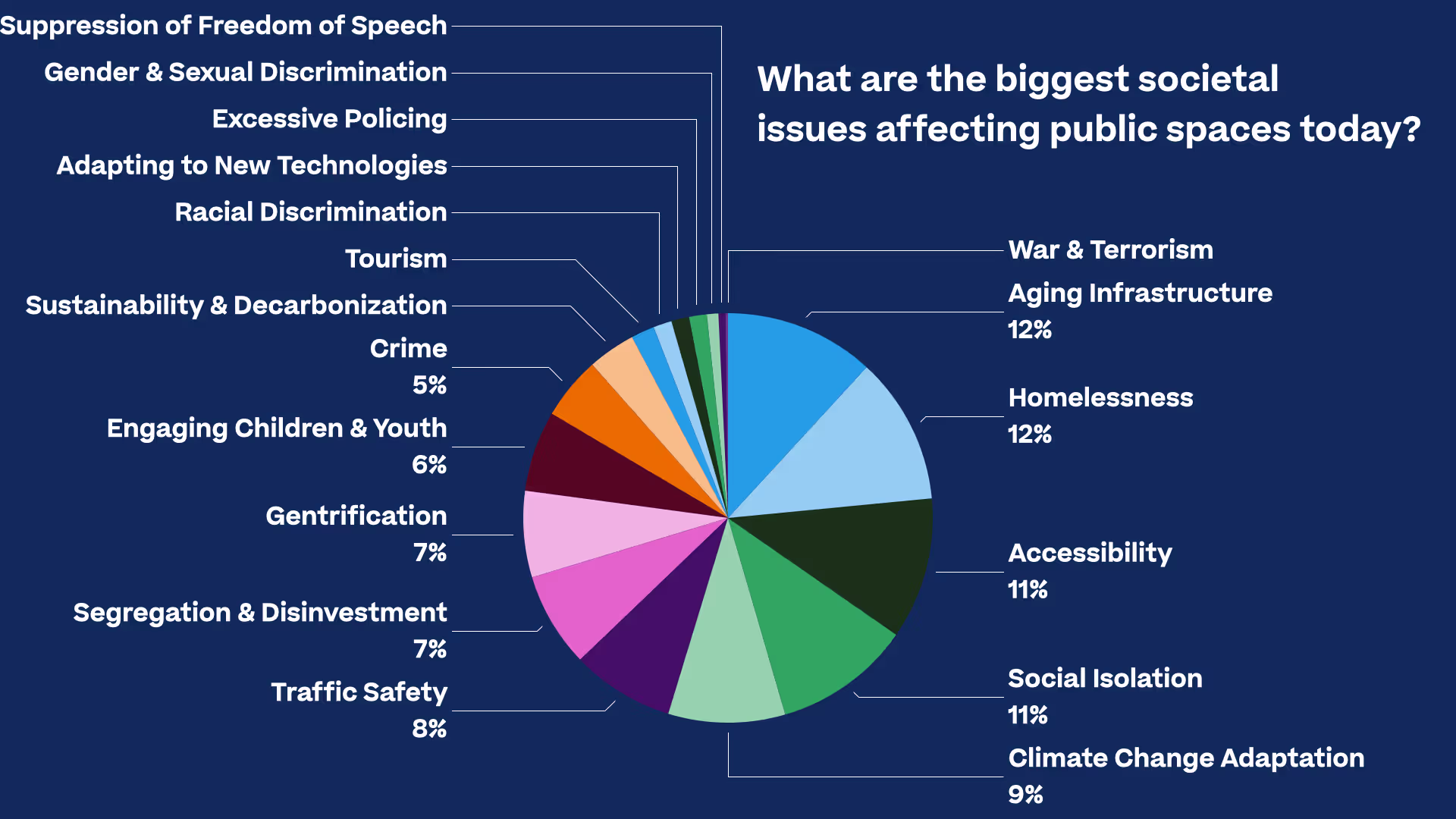

To dig deeper into why public space isn’t living up to its potential, we asked respondents to identify the biggest societal and practical issues facing public spaces today from a wide range of options. In the following sections, we break down seven big takeaways from these responses, drawing in insights from respondents, underlying trends, and innovative case studies to better understand what the data is telling us about the state of public space in 2025.

1. Aging Infrastructure

The way we fund public space is broken.

When celebrated urbanist Jane Jacobs was invited to speak at the White House in 1964, she decided to focus on what she called “a great unbalance” between money for building things and money for running things. Through 50 years of experience studying and improving public spaces around the world, Project for Public Spaces has found that the four characteristics of successful public spaces rely heavily on maintenance, programming, small regular design improvements, and ongoing community engagement—and yet, “running things” continues to be the hardest activity to secure funding for.

In the more than six decades since Jacobs’s speech, this great unbalance has only become more noticeable as budgets for parks, libraries, and even infrastructure have shrunk significantly. As a result, nearly 12% of respondents identified “aging infrastructure” as one of the top issues facing public space. When we think of aging infrastructure, we may jump immediately to roads and bridges, but public spaces are our civic infrastructure—the networks of community places that support our public health, resilience, and local economies.

To that end, public spaces need new funding models that recognize their need for gradual money, rather than money floods and droughts. What if more foundations and corporate social responsibility programs committed to investing in an open-ended placemaking process or to long-term public space initiatives? What if one percent of all federal infrastructure and housing spending supported nearby public space improvements? In cities with regular sporting or entertainment events, what if a small surcharge went to supporting local public spaces?

The ideas are out there and awareness of public space has grown significantly since the pandemic, but at the end of the day, this shift will require bold leadership in the public, private, and philanthropic sectors to fix the way we invest in some of our most undervalued infrastructure—civic infrastructure.

2. Bureaucracy

Cutting red tape could make limited resources go further in public space.

Aging infrastructure and underperforming public spaces are not only about money. After funding for capital improvements and operations, respondents said the greatest practical issues facing public space were political will and bureaucracy, together making up a whopping 31% of responses.

When it comes to funding, the question of how that money shows up often matters as much as how much. Perhaps because it fulfills so many purposes and crosses so many jurisdictions, public space often falls between the cracks of funding priorities like economic development, arts and culture, transportation, and even parks and recreation. As a result, public space improvement projects are often ill-suited to typical grant timelines and reporting requirements due to their open-ended nature, the uncertainties of implementation, and the need for ongoing upkeep. Likewise, government grants often have strong restrictions on the types of expenses that are allowed, such as supporting planning and technical assistance but no implementation or vice versa.

Even when financial support can be found, countless little improvements to our public spaces never happen because of red tape. Dealing with questions of zoning, permitting, and liability stifle many community efforts before they even get off the ground. For example, why do so many vacant lots never become something useful to the community? Untangling the messy records of property ownership often prevents action.

Simplifying and streamlining these arcane state and local government systems could unlock the potential of motivated public space professionals and community members to take on this work themselves. The City of New York, for example, appointed Ya-Ting Liu as its first Chief Public Realm Officer in 2023, after years of advocacy led by the Municipal Art Society and New Yorkers for Parks. The position’s role is to create a common vision for the city’s public realm to guide and support the dozens of public agencies and hundreds of nonprofits involved in the management and improvement of public spaces across the city. Today, the local Alliance for Public Space Leadership, of which Project for Public Spaces is a member, continues to support Liu in her efforts while pushing for increased investment across the city and tackling these ongoing bureaucratic hurdles.

In the coming years, we hope to see more cities adopt this model, but it will likely take local coalitions of community members and nonprofit organizations advocating for change.

3. Homelessness

Public space is on the frontlines of the housing crisis.

While homelessness is first and foremost about the people experiencing it directly, some of the most visible signs of the crisis are experienced by the general public in public space. Mental health crises, biohazards, maintenance issues, reduced access, and fear of crime—whether backed up by the data or not—have become an increasingly and disturbingly normal part of the public realm since 2017. As a result, 12% of respondents point to homelessness as one of the top issues facing public space today.

Among respondents, there was broad agreement on the negative impacts and the need to address the underlying housing crisis, however the suggested solutions from respondents varied drastically, reflecting national political divisions. Many stressed the need for affordable housing programs and improved access to social services, while some emphasized personal responsibility and increased law enforcement.

However, the evidence on the effectiveness of different strategies is clear. Firstly, as William H. Whyte observed in The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, often efforts to displace people experiencing homelessness make our parks, streets, and public buildings even more unwelcoming. Out of desperation, municipalities and place management organizations fill our public spaces with hostile architecture—removing seating, locking down or eliminating amenities that could be damaged or stolen, making sittable and lie-able surfaces uncomfortable, and sometimes blocking access to spaces altogether. These physical interventions are complemented by increased police and security presence, and this has grown even further in the United States since the Supreme Court’s 2024 Grants Pass decision, which gave localities the power to arrest, ticket, and fine people for sleeping on public property. Altogether, this security-focused approach rarely leads to well-used, well-loved public spaces. Instead, it transforms a city’s public realm into what one survey respondent called “a City of Fences,” while exposing our unhoused neighbors to harm and suffering.

So what should public space professionals do? In Project for Public Spaces’ work on the ground in Atlanta’s Woodruff Park and New York’s Times Square, we have found that partnerships between place management organizations and social service providers can help build the trust necessary for outreach efforts to successfully connect people that spend significant time in public space with shelter, social service programs, and eventually, permanent housing.

As we know, though, this frontline work is only part of the solution. Successful outreach only matters if our communities have a robust but less visible “continuum of care,” which coordinates the activities of local governments and nonprofits to ensure people have the support they need to find stable, affordable housing. As our colleagues at Brookings Metro have found in their research, these evidence-based strategies are typically less expensive and more enduringly effective than the security-based alternative.

We know that making and keeping public spaces vibrant and welcoming requires skills and knowledge from many disciplines. To address the homelessness crisis, placemakers must broaden their circles of collaboration to include strong social service partners, as well as organizations committed to addressing the root causes of homelessness.

4. Access

Physical, financial, and cultural barriers prevent many from accessing the benefits of public space.

With Access & Linkages being one of Project for Public Spaces’ four key elements of great public spaces, we were not surprised that this issue was top of mind for 11% of respondents. As the Trust for Public Land estimated, during the pandemic 100 million Americans lacked access to parks and green space at the moment when they needed it most.

Access is, of course, partly an issue of where public spaces are located. Low-income neighborhoods and communities of color simply have 44% less park space than whiter and wealthier areas. Identifying and transforming school yards, vacant lots, and other unconventional spaces into welcoming green space through placemaking is one way to help fill this gap.

But proximity to public spaces isn’t enough. A lack of universal design, a cost to enter or participate in events, and communications or programming that fails to reflect the community can broadcast to many people that a space is not for them, even if it’s close by. In short, belonging is an important dimension of access.

The quality of the walk, bike, roll, or transit ride also contributes significantly to whether people feel like they have access to public space in their daily lives. A 2023 study by the National Recreation & Park Association found that an estimated 97 million Americans that technically live within walking distance of a park still reported not having walkable access to a park. Streets themselves make up 80% of all public space in most cities, and despite years of progress in promoting active transportation, most streets in the United States still serve a single purpose: to move and store cars. To improve public space access across our cities and towns, departments of transportation must recognize Streets as Places. Integrating more non-mobility uses, like socializing, commerce, and programming, as well as the infrastructure to back it up, often ironically makes journeys feel shorter for everyone outside of a car than if we only optimized streets for multimodal movement alone.

The 34th Avenue Open Street in Jackson Heights, Queens—the longest open street in the United States—offers a model for addressing a significant lack of open space head-on, by transforming a busy, densely populated area into a vibrant, pedestrian-friendly environment, similar to Barcelona’s famed Superblocks. Community organizers host free English conversation classes, cumbia and salsa workshops, arts and crafts, clothing exchanges, and more, open to everyone. Meanwhile, this street also safely connects children to their schools and older residents to their everyday needs. This project breaks down many of the physical, economic, and cultural barriers that limit who has access to civic infrastructure.

5. Social Isolation

Public space can break the vicious cycle of loneliness.

In 2024, the US Surgeon General issued an alarming report on social isolation, which compares its health effects to smoking 15 cigarettes a day, and recommends strengthening civic infrastructure like parks, plazas, and public markets as its #1 solution. Reflecting this growing recognition of our epidemic of loneliness in the United States and beyond, social isolation was identified by 11% of all respondents as a major societal issue negatively impacting public spaces.

Journalist Diana Lind has gone as far as to argue that following the Covid-19 pandemic, American society may have entered a "Human Doom Loop," where an increasing reliance on virtual interactions has led to the decline of our real, shared spaces, which in turn pushes us indoors and toward life online. The end result is a vicious cycle of loneliness.

In order to break this cycle, people will have to change their relationship with both technology and the built environment. But public space professionals are best positioned to bolster use and care for our “third places,” the naturally occurring civic infrastructure of our communities, from parks to coffee shops to community gardens. As a recent report by Gehl Architects observes, this can be done by identifying the networks of “havens, hubs, and hangouts” in our communities, initiating placemaking projects to fill the gaps, and measuring social connection as a key outcome. This approach is especially important for young people, who are developing their relationships with technology and often feel unwelcome in public places.

By intentionally designing spaces where people can bond, interact across different backgrounds, and casually engage with one another, we can create environments that combat isolation and promote social health.

By intentionally designing and managing outstanding spaces where people can bond, interact across different backgrounds, and casually engage with one another, public space leaders can create environments that combat social isolation and out-compete virtual life as a way to spend our free time.

6. Climate Change

Extreme weather is making public space less welcoming, but public space can adapt.

Much like social isolation, extreme weather has created a vicious cycle for public space that must be broken. As hotter summers, the polar vortex, and greater risks of fires, storms, and floods hit cities around the world, public spaces become less accessible and less hospitable, further contributing to the Human Doom Loop.

However, while international respondents to the survey ranked climate change as their second highest priority at 12%, for American public space professionals, it ranked sixth, at only 8%. The United Nations’ “Sustainable Development Goals” are a common topic of conversation among urbanists around the world, but American professionals, governments, and organizations have largely opted out of this coordinated effort. This is despite the increasing frequency of extreme weather events like the droughts that hit the entire United States across 2023 and 2024, Hurricane Helene in 2024, and the Los Angeles wildfires in 2025.

The good news is that when we treat public space as a citywide network, it has the potential to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change, even beyond its already large footprint.

For example, one reason flooding gets so out of hand in urban areas is that impermeable surfaces cause water to accumulate and pick up speed. Permeable surfaces, and better yet, rewilded wetlands in public space can help absorb this water. Likewise, increasing shade, especially from tree canopy, and replacing dark-colored surfaces with plantings can help reduce the urban heat island effect, which worsens the effects of heat waves.

When storms, fires, and other extreme weather strikes, public spaces often become ad hoc logistical centers for disaster response and relief because of their central locations, flexible spaces, and recognition as the heart of the community. These public spaces could be even better integrated into resilience planning. For example, during the coronavirus pandemic, public markets proved their immense flexibility in distributing food under challenging circumstances while also supporting local food systems that are less vulnerable to global supply chain disruptions. This despite the fact that in many areas these same markets were shuttered because they operate under relatively insecure event permits, even if they’ve been doing so for over a decade.

Successful adaptation to climate change will require not only physical resilience, but social resilience. In his book, Palaces for the People, Eric Klinenberg argues that the future of democratic societies hinges on shared spaces like libraries, parks, and community centers where vital connections are made. Coining the term "social infrastructure," he highlights how these places play a pivotal role in addressing society’s most pressing challenges, including climate change. Notably, Klinenberg’s groundbreaking work on social capital built upon his earlier study of the 1995 Chicago heat wave, where he found that neighborhoods with a public realm built for social life were better prepared to help the most vulnerable in times of need.

In other words, both in the United States and abroad, our crises of social isolation and climate change are deeply intertwined, and must be addressed together in public space.

7. Disinvestment & Gentrification

Big public space investments need a plan for development without displacement.

Public space investment around the world is not distributed evenly or fairly. As a result, the practical and societal issues described above are more severe and concentrated in some communities than others.

In our survey, this fact was driven home by respondents who identified as North American people of color, who ranked “Segregation and Disinvestment” as their third greatest societal issue affecting public space (11%). These responses noted that communities of color receive less investment in public space creation, upkeep, and programming. Furthermore, these communities often have less capacity to create their own private place management organizations, like business improvement districts or park conservancies, to fill the gaps. Many of these same factors came up for respondents from American rural communities and informal settlements abroad as well.

However, “Gentrification” ranked as the second greatest issue among the same group (11%), as many respondents shared concerns that reinvestment could trigger displacement. Because public space has such a powerful effect on quality of life, even well-intended improvements can have a ripple effect on real estate and demographics that can disrupt existing communities as well as support them, both economically and culturally. Existing residents get priced out by the rising cost of living, but just as important is a diminishing feeling of belonging caused by changing cultural offerings and social dynamics, including hostile acts like targeted noise complaints. The word “placemaking” itself can raise alarm bells for some community members, leading to the useful sister term “placekeeping,” which emphasizes the value of sustaining existing communities, cultures, and the land, rather than transformation.

A new generation of public space improvement projects may show the path toward addressing these inequalities while preventing displacement. For example, the Crenshaw neighborhood of Los Angeles is a historically Black community that has faced disinvestment for generations. When LA Metro decided to construct a railway from the LA International Airport to downtown, the prospect of a new Crenshaw station predictably spurred an influx of private investment, raising the specter of displacement.

Destination Crenshaw was founded to capture this value for local stakeholders and ensure the area continues to be a thriving hub for Black culture. By 2022 it had attracted $70-90 million in investment. A recent report by LISC found that their neighborhood-wide approach, which combines both cultural and economic considerations, can help ensure longtime residents benefit from reinvestment. Helping local developers and business owners “buy back the block” will help Black Angelenos not just remain in the neighborhood but build wealth, while placekeeping strategies help the neighborhood manage change and continue to feel like the Crenshaw longtime residents remember.

Ultimately, this integrated economic and cultural approach to development without displacement could even help address the intergenerational inequality facing communities of color in the United States, informal settlements abroad and rural communities everywhere.

Looking Ahead: Public Space Inspirations for 2025

Since closing the survey in 2024, we have entered a new year that has brought even greater challenges for public space professionals. A new wave of scrutiny on federal funding in the U.S. has led to grant delays and proposed funding cuts, undermining the stability of the civic infrastructure that we all depend on. This has already resulted in worsening homelessness and chaos in our National Parks, and if these cuts continue we expect them to trickle down into neglected parks and streets, communities unprepared for this year’s floods and fires, and ultimately, a deepening spiral of social isolation.

But as we look ahead, we must also look to one another. Getting things done together locally, and collaborating across our cities and towns can be powerful. So while our public spaces face great challenges in the year 2025, there is also reason for hope.

Click on a symbol to see a link to the project, as well as any comments that respondents left about this place or project. To see the legend click the icon in the top left. Uncheck layers to see specific types of places and projects. See map in full screen.

As part of the State of Public Spaces Survey, respondents recommended 375 public spaces and placemaking projects that inspired them, including parks, plazas, trails, streets, markets, public buildings, districts, pop-up projects and events, infrastructure reuse projects, and policies and programs.

As Project for Public Spaces celebrates its 50th anniversary during this uncertain year, these bright spots demonstrate both the value that great public spaces already bring to people around the world, as well as the ingenuity of our community of public space professionals and advocates, dedicated to bringing this joy and meaning to more people.

Support Our Mission

Project for Public Spaces' 50th anniversary is a milestone that underscores the enduring impact of public spaces and our unwavering commitment to this vital mission. We invite you to help us support the next 50 years of public spaces by making a tax-deductible contribution to directly support our work in inspiring and mobilizing the next generation of public space leaders!